Click here to check out the large spread on Thacher Climbing that ran in the Times Union this Sunday.

Thacher cliffs call to climbers

This year’s opening of Thacher Park’s bluffs draws scores of rock-jocks — up to 60 a day on some weekends

Mike Whelan has climbed in spectacular settings all over the United States and on four continents, but he has a special place in his heart for the limestone cliffs at Thacher State Park.

He grew up just 20 miles away in Duanesburg. When he was a youngster, he visited Thacher with a friend who showed him a few rock-climbing moves. The boys didn’t actually climb — they lacked equipment, and besides, the park prohibited climbing — but a seed had been planted.

In his early 20s, Whelan took up climbing in earnest, usually traveling to the Gunks — short for Shawangunks — a renowned climbing destination a few hours south of Albany. He became so enthralled with the sport that he eventually moved to Boulder, Colo., which he describes as the nation’s “epicenter of climbing culture.”

Whelan, now 35, didn’t forget his roots. In 2012, he founded the Thacher Climbing Coalition, lobbied park officials, and finally, after years of hard work, saw his dream come true: Thacher opened some of its cliffs to climbers this past summer.

“It was an effort to diversify the activities in the park to appeal to a greater number of people,” said Alane Ball Chinian, the regional director of the state Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

Ball Chinian is pleased with the results of the first season. Since July 1, Thacher has seen 45 to 60 climbers a day on the weekends. In all, about 750 climbers visited the park through Oct. 18. They came from 26 states and from countries as distant as Spain and China. “It’s great for tourism. It’s great for economic development,” she remarked.

Park officials worked with the coalition to determine where climbing could occur without harming rare plants or interfering with other park users. They agreed on some ground rules and then left it up to the climbers to establish the routes. Many climbers were involved, but Ball Chinian singled out Whelan and Jeff Moss, the coalition’s current president, for special praise. “This would not have happened if we did not have an outside group assisting us,” she said.

Thacher is only the third New York state park to allow climbing. The other two are Minnewaska State Park, near the Gunks, and Harriman State Park, a bit farther south. Minnewaska has permitted climbing since 1996, Harriman since 2013. A spokesman for the state parks office said the agency is “very open” to allowing climbing in other parks where appropriate and where a climbing organization gets behind such an initiative.

The new policy at Thacher is especially good news for climbers in the Capital Region. They used to have to drive to the Gunks or Adirondacks for a day of climbing. Now they have a crag so close to home that they can head there after work to get in a few hours at the cliff.

“We’ve already seen a lot of locals, and I expect that we’ll see more as word gets out,” said Monica Moss, vice president of the Thacher Climbing Coalition.

Not that Thacher State Park will ever replace the Gunks or the Adirondacks. The Gunks, located outside New Paltz, boasts more than 1,300 climbing routes. The Adirondack Park has more than 3,000 (albeit spread among hundreds of cliffs). At the moment, Thacher has only about 50 routes. But Whelan expects the number to grow to 120 or so over the next few years, and he holds out hope that someday more of the Helderberg Escarpment, of which the Thacher cliffs are a part, will be open to climbing.

Thacher differs from most climbing areas in the Northeast in that the rock is limestone, formed from sediments of ancient seas. Marine fossils, such as trilobites and crinoids, abound. Unlike the anorthosite in the Adirondacks, say, or granite in New England, the limestone has few cracks — a circumstance that influences the style of climbing.

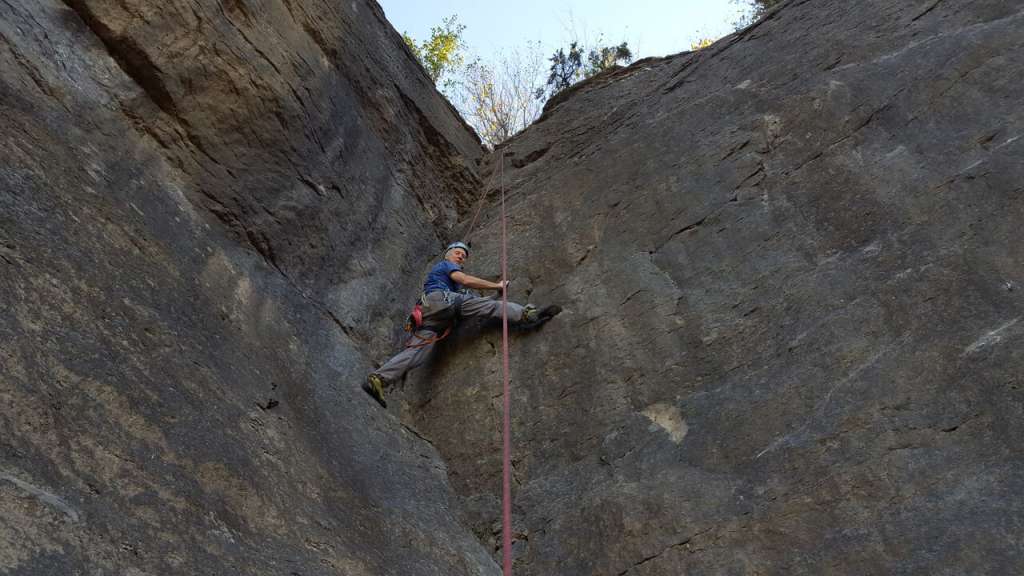

Typically, rock climbers protect themselves by clipping their ropes to camming devices, or chocks, that they fit in cracks as they ascend. A belayer keeps the rope taut, so if the leader slips, he or she will fall only as far as the last piece of protection (assuming the gear doesn’t pop out). This is known as trad climbing — short for traditional. Most of the climbing in the Northeast is trad.

At Thacher, the routes are bolted. As climbers ascend, they clip the ropes to stainless-steel hangers. At the top of each route is a set of chains and rings through which the rope can be threaded for lowering. This is known as sport climbing. All other things being equal, sport climbing is easier and safer than trad because the climber doesn’t have to place protective gear.

Sport climbing is especially appealing to climbers who want to push their limits without having to fiddle with cams and chocks. It also appeals to those who learned to climb in a gym, where all the gear is likewise fixed, and who want to transition to real rock.

Thacher has another similarity to gym climbing: the routes are short. Most are about 50 feet, and none is longer than 90 feet. Short, however, does not mean easy. The majority of the routes are steep, with small holds, and doable only by experts. Fortunately for us mere mortals, there are plenty of moderate routes as well.

In mid-October, with fall colors nearing their peak, Whelan took me on a tour of Hailes Cliff South and Horseshoe North, the only cliffs where climbing is allowed. They are located a short drive from the park’s new $4 million visitors center, which opened in May. Climbers are required to register at the center and pay a $6 parking fee.

Getting to the bottom of the cliffs proved to be an adventure. We had to squeeze through a sloping slit in the earth known as Helmus Crevice. At its narrowest, the crevice is little more than a foot wide. Whelan wiggled through after removing his pack. I, however, got stuck. “Suck in your stomach and exhale, like a caver,” Whelan advised.

Alas, I’m not a caver. Eventually, I resorted to a crab walk, shuffling along on my butt beneath the pinch point.

Whelan led me along the base of Hailes Cliff South to a side path marked by a cardboard sign that read “Mahican Wall,” a reminder that this climbing venue is a work in progress. “I’m hoping someone volunteers to make us some wooden signs,” he remarked.

We warmed up on one of the easiest routes at Thacher, a short corner climb with lots of big holds. Next we ambled over to Tossin’ ze Chossin’ — the first route established at Thacher and considered one of the best. It follows a longer, steeper corner that offers climbers a chance to employ a variety of climbing techniques.

Later we hiked the quarter-mile or so to Horseshoe North, where we did four other climbs. We stopped to chat with Lisa Lim and Jenna Spitz, who had driven from Philadelphia after learning about the park from climbing groups on Facebook. They were doing a route on the Fossil Wall.

“Did you see the trilobite?” Whelan asked.

“Yes, that’s why we climbed here,” Lim said.

Spitz enthused about the scenery. The late-afternoon sun had illuminated the paper birch in the valley below the cliffs. The sky was virtually cloudless, enabling us to see all the way to the Empire State Plaza. “The view is incredible,” she said.

That view is one reason Whelan keeps coming back — all the way from Colorado.

“For me, aesthetics mean almost as much as climbing,” he said. “I just love being outside. It doesn’t matter if it’s hiking or climbing.”

Phil Brown is the editor of the Adirondack Explorer, a magazine that focuses on environmental issues and outdoor recreation.